Ethnomycology

1. Common names of fungi

3. Fire and clothing made from tinder fungus

The term ethnomycology describes the study of the historical heritage and sociological impacts of fungi by mankind and can be seen as a section of ethnobotany and ethnobiology. The term includes topics such as fire-making with the tinder fungus and applications in folk medicine. The use of mushrooms with psychoactive substances such as the toadstool can be a research topic, too.

We would like to provide information and links on the topics of tinder-craft and mushrooms as food.

AIGNER & KRISAI-GREILHUBER (2016) have published a study on the mushroom knowledge of the population of the Waldviertel. The Waldviertel is part of the Bohemian Forest project area, so there is a certain transferability of the results, subject to regional differences in the types of mushrooms, common names and kitchen recipes used.

1. Common names of fungi

The following wisdom is used in mycology: "The common names change from place to place, the scientific names from time to time".

To confirm this wisdom we would like to give you the well-known common names of the chestnut bolete

and show the history scientifically valid names over time:

In 1818 the first description was made by Elias Magnus Fries Boletus castaneus ß badius Fr. 1818. Then followed:

Boletus badius (Fr.) Fr. 1821

Boletus badius var. castaneus (Fr.) Fr. 1828

Boletus glutinosus Krombh. 1836

Boletus vaccinus Fr. 1838

Rostkovites badia (Fr.) P. Karst. 1881

Viscipellis badia (Fr.) Quél. 1886

Ixocomus badia (Fr.) Quél. 1888

Suillus badius (Fr.) Kuntze 1898

Boletus badius var. glutinosus (Krombh.) Smotl.

Tubiporus vaccinus (Fr.) Ricken 1918

Xerocomus badius (Fr.) E.-J. Gilbert 1931

Imleria badia (Fr.) Vizzini 2014

We know of common names (vgl. ZEITLMAYR 1955):

Blaupilz

Braunkappe

Bräunl

Frauenschwamm

Graspilz

Marienpilz

Maronen-Röhrling

Marone

Nadelstreu-Maroni

Schafsschwamm

Schmalpilzl

Tannenpilz

Weishedl

Literature cited:

ZEITLMAYR L (1955): Knaurs Pilzbuch von Linus Zeitlmayr mit 70 farbigen Pilzbildern von Claus Caspari. München.

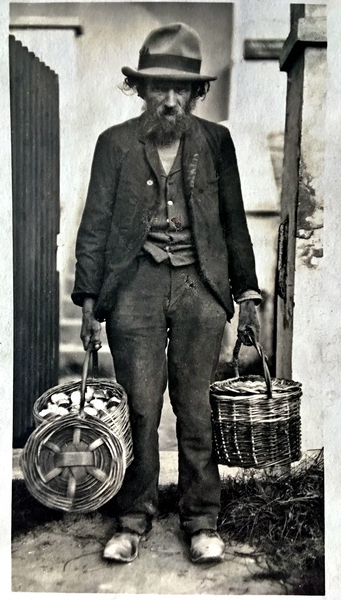

2. Edible mushrooms

Mushrooms have been used as food since the Paleolithic Age. In the history of mycology in the Bohemian Forest, it is pointed out that many mushroom amateurs, mycology-related interest has arisen in many cases by collecting mushrooms. In Europe there are countries and regions that are referred to as mycophilic and those that are considered mycophobic. The entire Bohemian Forest is clearly mycophile, empirical knowledge has developed here over the centuries-old use of mushrooms as food from the forest.

picture: Bildarchiv und Verlag Sebastian Winkler-München

Among the more than 4.200 species of fungi shown here, there are between 150 and 300 edible mushrooms, depending on the rating. More than 250 species are classified as poisonous, at least 12 species of fungi are highly damaging to organs and can be fatal without medical help.

Since realms of publications in the literature and Internet deal with the subject of edible mushrooms, we would like to recommend only a few further links here, combined with the note that there is also a large number of articles and websites with dubious content on the Internet. So when it comes to the identification and use of mushrooms for food, please always use common sense and only reliable sources. Unknown species of mushrooms are potentially deadly poisonous, which means that mushrooms that are recognized as edible and fresh only definitely belong in the cooking pot. In Germany you will find useful information, contacts to mushroom experts and associations on the topic of mushrooms on the website of the German Society for Mycology. In Austria the same applies to the ÖMG. In the Czech Republic, mushroom fans can get information from the Czech Mycological Society. There is also an information page about toadstools.

Nowadays, mushrooms also have a variety of uses as a delicious and healthy change on the menu, even beyond "folk nutrition". There are hardly any limits to the creativity in the kitchen if it is not the classic "Bohemian mushroom goulash". Today everything goes according to the motto "wild mushrooms as healthy superfood, not cheap fillers".

picture: Tanja Major

picture: Tanja Major

If you don't dare to go alone and have no experts in the circle of friends, you can take courses for beginners such as of the MushroomCoach training.

At this point we would like to present a selection of mushrooms and unedible poisonous doubles. You can find detailed descriptions of all known mushrooms from the Bohemian Forest here.

When using images to determine, please consider that mushrooms of one species can look very different depending on maturity and water content. A list of edible mushrooms recommended in Germany can be found here.

Several species of mushrooms are assessed regionally and individually differently. These species can be found in a further list.

As a mushroom collector, you should also familiarize yourself with the sometimes life-threatening types of toadstools. Depending on the definition and dosage, there are certainly more than 300 types of toadstool in the project area. Below we show a selection.

picture: Dr. Matthias Theiss

picture: Gerhard Schuster

picture: Dr. Matthias Theiss

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Dr. Matthias Theiss

picture: Michaela u. Gernot Friebes

picture: Michaela u. Gernot Friebes

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Gerhard Schuster

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Michaela u. Gernot Friebes

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Gerhard Schuster

picture: Felix Hampe

picture: Gerhard Schuster

picture: Gerhard Schuster

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Jesko Kleine

picture: Michaela u. Gernot Friebes

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Jiří Kubásek

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Jesko Kleine

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Petra u. Werner Eimann

picture: Gerhard Schuster

And of course there are significantly more edible wild mushrooms than porcini, chestnut and chanterelle in the Bohemian Forest. Depending on the individual definition, more than 300 species of mushrooms in the region (sometimes only in small quantities) are probably suitable as edible mushrooms. Please also note that very few of them are easily digestible. We recommend a cooking time of at least 15 minutes at 90 degrees Celsius. Some species such as the honey fungus (Armillaria mellea agg.) Should be pre-cooked in boiling water for 5 minutes before preparation.

poisonous mushrooms belong to the agarics or lorels.

picture: Tanja Major

The following selection is not to be regarded as a general recommendation for consumption. Some species may be legally protected regionally. According to our knowledge, the somewhat chewy yellow stagshorn (Calocera viscosa) is only used in mixed mushroom dishes in the Czech part of the Bohemian Forest. Some species such as some psalliota (agaricus) accumulate heavy metals or such as e.g. the chestnut bolete of radioactive substances. Individual intolerance or allergic reactions are also possible. It is recommended to taste only small amounts of one type of mushroom the first time. As with other foods, the rule is "the dose makes the poison"

picture: Peter Karasch

picture: Peter Karasch

3. Fire and clothing from the tinder fungus

The tinder fungus (Fomes fomentarius), also known as Huder- or Hodersau in the Bavarian Forest, was already the mushroom of the year in Germany in 1995.

It's use in ecosystem as a natural indicator, it's application in naturopathy and the millennia-old tradition of making fires as well as clothes and cleaning rags (Hodern).

The widespread use in fire production with flint and steel was only ended with the invention of the matches. Nowadays archaeologists and outdoor enthusiasts are inspired about the old technique of fire production.

The world's best-known user of the Huder- or Hadersau, as the polypore is called in the Bavarian Forest, was Ötzi, the best-researched Stone Age mummy in the world. Of course there were tinder sponges long before Ötzi’s birth. In 2009, Kreisel & Ansorge reported in the journal for mycology about what was probably the largest ever documented subfossil fungal fruiting body. It came from an pit near Stralsund and was dated to around 7300 years. Since the oldest known ancestor of beech (Fagus pliocenica) have been preserved as fossils from the tertiary, it is quite possible that tinder fungus have existed on earth for more than 3 million years. It was no coincidence that Ötzi also had the tinder with him. It is well known that until the matches were developed around 180 years ago, the easiest way to make a fire was with steel and tinder. Fire was made with forged steel, flint and tinder and the burning embers were kept. You could also transport smoldering tinder in a jar for some time. The term tinder includes all types of flammable materials, e.g. prepared reed mace seeds. However, almost all prehistoric evidence shows that the tinder sponge is the most common material used. The ancient practice of carrying the easter fire from place to place with burning tinder has survived to these days.

The tinder fungus occurs in the entire northern hemisphere, eastwards over Russia to Mongolia (also India, Pakistan) and westwards in North America. Since the favorite substrate of the tinder fungus is beech, it has a very large area here (see www.pilze-deutschland.de). Birch is the second most common host tree, but as a fast-growing pioneer plant it has significantly smaller fruiting bodies than old giant beech trunks. Other types of hardwood such as hazel, cherry and walnut are less common. The frequent occurrence of tinder fungus in forest areas is a good indicator of their conservation value. There he is considered a indicator of nature value and infects weakened trees as a parasitic fungus. After the infestation, he can live for a while as a saprobiont in the affected wood and generates fruiting bodies that are up to 30 years old. In an early stage it begins as a hemispheric outgrow and usually develop in a console shape up to 10-30 (60) cm in diameter. New rings are formed in each growth phase, between two and three per year. If a standing dead tree and its fruiting bodies fall over, the fruiting bodies continue to grow towards the geocenter, which sometimes leads to interesting shapes. If you are looking for and “find” tinder fungus on e.g. coniferous trees such as spruce, you probably have his double, the red banded polypore (Fomitopsis pinicola) in your hand.

Old specimens in particular can look illusively similar on the top, but a cut through the tough consoles is enough to distinguish the rust to tobacco-brown tissue of the tinder bracket from the lighter red banded polypore. If you have a lighter with you, you can also make the flame test on the top of the upper surface in case of doubt. The varnish-like outer layer melts in the red banded polypore. By the way, the tinder fungus produces a white rot in the wood through the breakdown of lignins, while the red banded polypore causes brown rot after the breakdown of cellulose.

Fomes fomentarius has been an important supplier of tinder to mankind since at least the Stone Age. To use it, you first have to peel the fresh fungus. The softer middle layer is then soaked, boiled, tapped, soaked in urine for a few weeks or treated with nitre and dried. The result of this complex process is a tobacco-brown felted mass that begins to glow when iron sparks strike. This process also has to be practiced, it becomes very difficult when the material is damp and the weather is damp.

Untreated tinder was made into "wound sponge". You could buy he wound sponge until the 19th century in pharmacies as a styptic dressing. Since the tapped and dried tinder sponge can be drawn and applied like felt, it was very utilize. Large pieces were made into garments. The production of robes made of tinder material is known from several dioceses. The need for tinder was so high at times that it was almost extinct in Germany and had to be imported from Eastern Europe. From the area around Todtnau (Black Forest) it is known that around 1830 there were still three tinder factories. As late as 1871, one of these factories manufactured 750 hundredweight tinder. Licenses for the tinder harvest were assigned by several forest districts.

It was only towards the end of the 19th century that the invention of matches replaced the tinder when making fire. This development was probably the rescue for the species and it's hosts, often noble old beeches. Now, instead of the fungus, an old craft and formerly important economic branch in Germany, has died out. Here and there, traditions such as the festival of charcoal burner and tinder tapper from Neustadt am Rennsteig in Thuringia. The Rennsteigmuseum has published what is probably the most extensive collection on the tinder bracket.

This craft has been preserved in Transylvania to this day. But even there, the number of artisans has shrunk to a few dozen in the past 25 years. The old technique is usually passed on from father to son within the families. Not least due to the creative DGfM-PilzCoach movement and a growing group of interested for "vegan leather", which in this case should probably be called fungan leather, there is a decent demand for tinder products in this country, so that the remaining artisans in Transylvania are well employed and also in Germany new creative ideas arise with this material.

The peeled tinder kernels are soaked in potash, boiled in leach and hydrochloric acid until they are soft. The pieces pretreated in this way are expansed by tapping (sponge tapper) and pulling to ten times the size. Then they are dried and further processed into hats, bags, table-cloths and small souvenirs.